News by

The Guardian on

There is an unforgettable photograph of a Soviet soldier raising the red flag over the Reichstag near the end of this momentous exhibition. The soldier crouches at a terrifying angle to hang his victorious banner above burned-out Berlin in May 1945. It is a famous shot – the figure high among the parapets beneath a thunderous sky – and known to have been staged, like the marines hoisting the flag at Iwo Jima. But in this context, one sees it completely new.

The photographer was Jewish. His father and sisters had been murdered by the Nazis. His uncle made the flag by hand, the hammer and sickle glowing an immaculate white almost at the epicentre of this dark image. And what has inspired Yevgeny Khaldei is not just the possibility of raising the figure high among the parapets, a worker on the same level as the imperial statues, but the dynamic geometries of Russian abstract art. His scene is all triangles and heroic diagonals, harking back to El Lissitzky and Malevich.

Mayakovsky said that a Soviet poster should be able to bring a running man to a halt

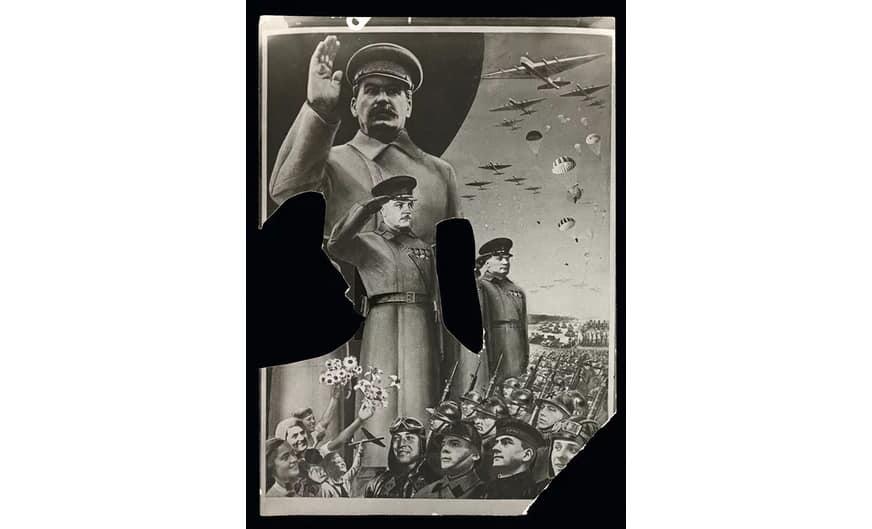

It would be hard to overstate the visual impact of Red Star Over Russia at Tate Modern. Selected from almost a quarter of a million graphic images zealously collected by artist and designer David King until his death in 2016, it is a condensed vision of five decades of Soviet hopes ending in devastation and despair. The range is phenomenal: from glamorous female fighter pilots to peasants studying Lenin in the fields, from a monumental Stalin watching Soviet planes fly past his eyes like gilded insects to athletes hurtling up the picture plane towards a finishing line of communist slogans.

Many images are on display for the first time, such as the grainy photographs of secret police emerging from the shadowy interior of unmarked vehicles to the notorious Bolshevik show trials of 1936-8, the victims about to be executed by the dazed young soldiers undergoing execution training in the neighbouring photograph.

The show opens in 1905 with the massacre of unarmed protesters by tsarist troops in St Petersburg. Bloody Sunday prompted some brilliantly mordant counterblasts – a gigantic skeleton shrieking its way through the snowbound streets; a square where the crowds turn out to be a throng of red skulls. With the revolution, these one-colour images have their heyday with the posters of the Soviet news agency Rosta, which enlisted some of the great artists of the time, including Aleksandr Rodchenko and the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky.

Perspective is radicalised; compositions tilt at sheer angles and in scimitar curves; the sans serif typeface and red, colour of the proletariat, predominate. Women are urged to vote and to fight, men to unite, their strong faces vast against the new industrial cityscapes. Hats become political emblems: capitalism’s slick top hat, the worker’s headscarf, the tumbling crown of imperialism. A marvellous image of Trotsky shows him in long red coat and military cap striding across the USSR, his very outline condensing the map of the motherland.

Mayakovsky said that a Soviet poster should be able to bring a running man to a halt. These posters were urgent news in graphic form for a largely illiterate country; they also brought modernism directly into the old culture of icons. They appeared in stations and cafes, on city walls and trams. It is staggering even now to witness this overlap between propaganda and the avant garde, the most famous instance of which is surely Lissitzky’s red triangle driving into a white disc against a burning black ground. Suprematism in the service of communism, its title (Beat the Whites With the Red Wedge) and its composition urge the Bolsheviks to beat the White Russians.

David King’s edition is torn in one corner. His archive is fragile and hard-won, especially the rare surviving images of Trotsky. What you see at Tate Modern is living history in mass-produced ephemera, some of it stencilled by hand when no printing presses were available. Creased and fading photographs capture the minutiae of everyday life as facts and statistics never can. Here is a Red Square march with an effigy of Lord Curzon paraded like a giant Mr Punch (he had just passed an anti-Soviet edict), and another where Lloyd George is lampooned in lifesize wooden cut-out. Look deep into the crowds and you will see anxiety and exhaustion, too, among the fervour.

Even when the workers are lined up alongside a caption claiming that they are the owners, rather than slaves, of the USSR, their uniforms occasionally look as worn as their faces.

King’s ambition was to balance truth against fiction. Which is literally the technique of Soviet collage, where past, present and future may be merged together; and also of photomontage, where pictures skimmed from the streets may be spliced with art. Lenin addresses the multitudes, and legible slogans coruscate from his mouth in megaphone rays. Factories fuse with fields that morph into shipyards manned with workers from all over Russia in fantastical montages. Stalin himself appears to be right there among the brave comrades building the metro.

But photomontage can make people disappear too. A sequence of images shows three commissars standing alongside Stalin gradually vanishing one by one, until only the despot remains; the murder of his opponents has an exact pictorial equivalent. And the murderers themselves might eventually disappear, scissored out of official group shots from the 1920s onwards, leaving menacingly conspicuous holes.

Ordinary citizens also did this in fear. King collected photographs where the faces are inked out or gouged from the print with a penknife. This is the dark obverse of everything that went before, in art as in life. The early hopes nourished by a generation of stunning graphic images end in the real and symbolic destruction of life.

Stalin crushed the avant garde and replaced it with socialist realist dross. With the second world war there is a slight revival of revolutionary posters (and even of the few artists who had escaped the purges), but mainly in weak pastiche. Mayakovsky’s dream of “a nation of 150 million being served by hand by a small group of painters” was over. There is a tiny photograph here – taken by whom? – showing Mayakovsky dead by his own hand, blood on his shirt, mouth horribly agape.

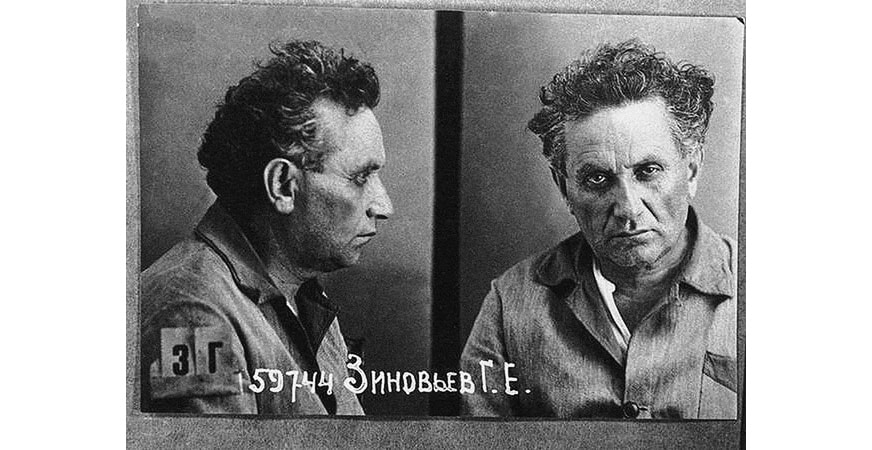

Red Star Over Russia is filled with such revelations. It is not theatrically installed so much as tightly curated to hold the eye fast to images of extraordinary significance and power. And for every magnificent fiction of workers uniting to overthrow tyranny there is a levelling truth. Stalin’s second wife, Nadezhda, slips furtively past on a Moscow street, brows down, not long before she kills herself. Photographs of the storming of the Winter Palace are shown to be heavily confected and retouched. The poster artists of the early days of the revolution reappear at the end of the show in secret police mugshots, on their way to disappearance or public death. And among them, most devastating of all, is the face of Grigory Zinoviev, once head of the Communist International. His show trial in 1936 ushered in the Great Terror, but he is not afraid. Instead, Zinoviev looks his fate in the eye with disillusioned anger.

Comments

Add comment