News by

KQED on

Like many Russian immigrants who came to the Bay Area in the 1990s, my childhood was full of weekly pilgrimages to San Francisco’s Richmond District. On Sundays, my family and I would get dressed up to attend Russian Orthodox church on Geary Street, buy olivier salad and pickled cabbage by the pound at New World Market and take in the aromas of pirozhki and other baked goods at Cinderella Bakery.

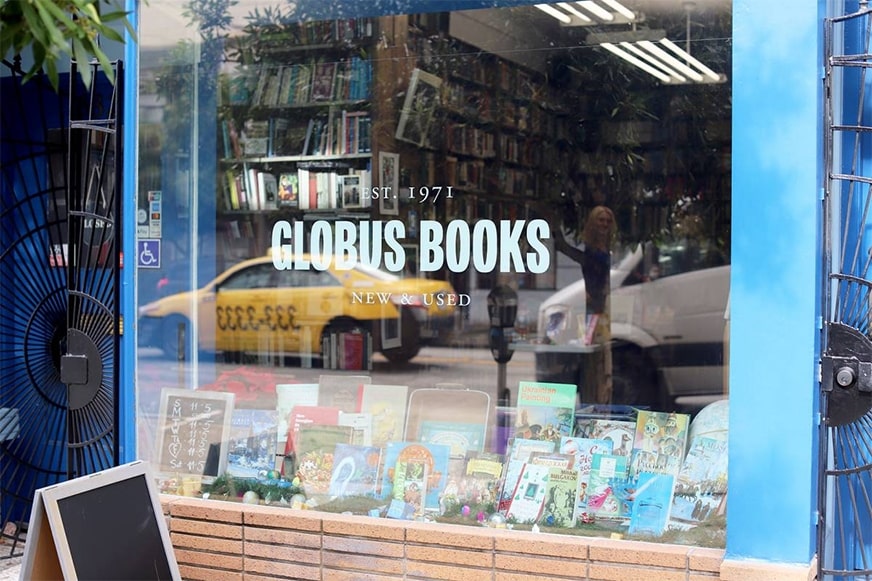

With bellies full, we’d stroll down Balboa Street to Globus Books, the Russian bookstore that feels like a time capsule, with its Persian rugs, towering shelves of dusty tomes and a distinctive old-library scent. As a child, I delighted in Soviet-era picture books like Dyadya Fyodor, about a precocious boy who runs away from home to live with a dog and cat. In my teen years, I explored intimidating stacks of classics by Dostoevsky and Bulgakov, and art books from the Hermitage Museum of my native Saint Petersburg. And in my early twenties, I tripped out on Victor Pelevin’s drug-addled, darkly funny Gen X novel Generation P (the P standing for pizdetz, or screwed).

Globus, opened in 1971, has remarkably stood the test of time, serving several generations of Russian immigrants, including those who came as Jewish refugees during the ’70s and ’80s, and the rest that followed after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Yet as the Richmond District changes, and as the Russian community gets priced out along with other immigrant populations in San Francisco, the decidedly niche business has found itself in need of switching up its approach as it enters a new decade, hoping to preserve its older generation of customers while attracting younger readers and non-Russian speakers.

For new owner Pavel Chepyzhov and managers Julie Kulyamzina and Zarina Zabrisky, that means embracing the diversity of the Bay Area’s Russian-speaking community, as well as people curious about Russian culture and literature.

“On one side you have Russian speakers who came from China after the second world war, and they are very different from the Russian speakers who are immigrating right now to Silicon Valley,” Chepyzhov offers, adding that Georgian and Armenian cultures also occupy a prominent place within the Bay Area’s Russian-speaking world. “They have a lot of books in common and Globus could be the place where they all could meet.”

Books about Russian feminism and LGBTQ+ people have also recently made their way onto Globus’ shelves. And the store now has a growing English-language section on Russia and the former Soviet Union. (On my last visit, I picked up Lydia B. Zaverukha and Nina Bogdan’s visually stunning Russian San Francisco, full of historical photos dating back to 1840.) One of the goals, Chepyzhov says, is to spread awareness about the culture beyond what Americans hear in the news.

“Unfortunately the Russian politics, of course, doesn’t get the best media for obvious reasons,” he says. “But I think talking about books and about culture—this is what we want to promote, this is what is appreciated in the U.S.”

Zabrisky, a writer known for her work with progressive activist group the Arts Resistance, is in charge of new event programming for the space, including author talks, readings and screenings coming later in the year. The first new event series is story time for toddlers, happening every Wednesday at 10:30am starting Feb. 5. It fulfills a core part of Globus’ mission to help Russian-speaking parents pass on their language and culture to the next generation.

“We’re in love with this bookstore, with its history, its accomplishments and what it is for the Russian community here,” says Kulyamzina.

She and Chepyzhov, both from Moscow, are antiquarian book specialists who spent the last several years frequenting Globus during trips to book fairs on the West Coast. Globus founder Vladimir Azar originally ran a publishing house focused on Russian immigrant authors, earning the shop a cult following among Russian-speaking bibliophiles around the world.

Last year, Chepyzhov learned that former owner Veronica Ahrens-Pulawski, who presided over Globus’ shelves since the early ’80s, was looking to retire and sell the business.

“It took me maybe 10 minutes to draft a plan in my head of how we could work together on that and try to keep Globus alive, and try to keep this business going,” he says, adding that Ahrens-Pulawski—whose dynamic personality has long been a draw for Globus’ loyal customer base—still helps out twice a week.

The new Globus team’s progressive vision is a rarity for the Russian-speaking immigrant community in the United States, which leans conservative; older generations who escaped communist rule have an aversion to anything that sounds remotely socialist. If San Francisco’s Russian newspaper Kstati (full of right-wing op-eds written in the key of “well actually”) is any indication, it’s likely that many of San Francisco’s Russian-speaking immigrants voted in the 2016 election along similar lines to those in New York’s Brighton Beach, the biggest patch of red in mostly blue Brooklyn.

Yet Chepyzhov says there’s more than enough room for diverse voices and perspectives at Globus. “It’s one of our goals to show the alternative side of things,” he says.

He points to portions of the Russian-speaking immigrant community that are rarely mentioned in the media—such as queer and trans asylum seekers escaping anti-gay laws. Reports of anti-gay purges came out of Chechnya as recently as last year, prompting international protests in solidarity. And in the Russian Federation, a 2013 law banning “gay propaganda” diminished LGBTQ+ people’s civil rights protections while legitimizing already-rampant homophobia within the culture.

“We try to do our bit supporting LGBT causes here and in Russia,” says Chepyzhov. “We would like to represent these people as well.”

Chepyzhov still lives in Moscow and comes to San Francisco to run the store for months at a time throughout the year. While he was away the last few months, Zabrisky and Kulyamzina gave Globus’ shelves a makeover. Books by neo-fascist Russian political strategist Aleksandr Dugin, for instance, have gone into storage, while a biography of Barack Obama and a history of change-making women in Russian history are now prominently on display.

“We don’t want to be censors, but we don’t want to promote views that are harmful to society,” says Zabrisky.

“We don’t want to scare away the customers who’ve been coming in for decades, we still have books for them,” says Kulyamzina. “But we also want to attract a new generation.”

Comments

Add comment