News by

The New York Times on

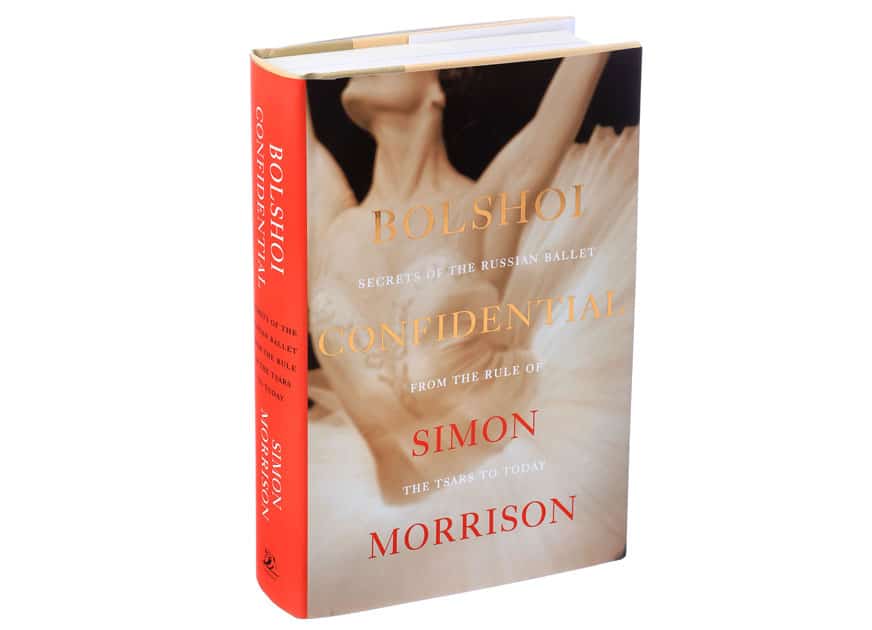

Simon Morrison’s “Bolshoi Confidential: Secrets of the Russian Ballet From the Rule of the Tsars to Today” delivers what its title promises: struggles and intrigues, crimes and punishments, imperial jewels and Soviet medals.

Based on extensive research in libraries and archives, and conversations heard at Russian kitchen tables, Mr. Morrison’s book gives a historical tour behind the scenes of one of the world’s most glorious ballet institutions, from 1776, when the Bolshoi was founded by Michael Maddox, an English adventurer in Russia, to the attack with acid on Sergei Filin, the Bolshoi’s artistic director, in 2013.

That this is a backstage view, a look through the keyhole, is both this book’s strength and limitation. The story of a big theater like the Bolshoi can only benefit from the combination of two perspectives: one that zooms in to look at the Bolshoi people, their lives and their roles; and one that zooms out to assess the part the Bolshoi has played in larger histories — of ballet as an art form and of Russian culture. The insider look in “Bolshoi Confidential” is incredibly rich and makes this book a page-turner; the moment it steps outside the Bolshoi, Mr. Morrison’s narrative becomes somewhat cruder and less compelling.

You would expect a book subtitled “Secrets of the Russian Ballet” to contain household names and famous titles that made ballet, as Mr. Morrison, a professor of music at Princeton, calls it, “the most Russian of the arts.” But if a book is about only the Bolshoi, most of these names and titles won’t be there.

Russian ballet is a tale of two theaters: the Bolshoi in Moscow and the Mariinsky (known as the Kirov from 1935 to 1992) in St. Petersburg, the imperial capital. And it is the Mariinsky, not the Bolshoi, that the majority of Russian-born ballet celebrities considered their home theater, from the legendary stars of the Ballets Russes (like Nijinsky and Pavlova) to the famous late-Soviet defectors (Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova, Mikhail Baryshnikov).

Maya Plisetskaya, to whom Mr. Morrison devotes a whole chapter, was an important exception: She was trained in Moscow and danced in the Bolshoi throughout her career.

Nor was the Bolshoi stage the cradle of many household ballet titles. The only foundational classical ballet that originated in Moscow was “Swan Lake,” the big flop of 1877. It was not until Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov choreographed it anew at the Mariinsky 18 years later that “Swan Lake” became something like the ballet we know. Moreover, despite the Revolution and the loss of its imperial status, the Mariinsky never conceded the race, not even when, with Moscow the capital of the Soviet Union, the Bolshoi found itself the regime’s favored showcase.

As often happens with the famously unpredictable Russian past, the Bolshoi retroactively has come to represent the entire Russian ballet, past and present. And its history has become a mixed metaphor of sorts: a story of the Russian ballet in a profoundly Soviet institution.

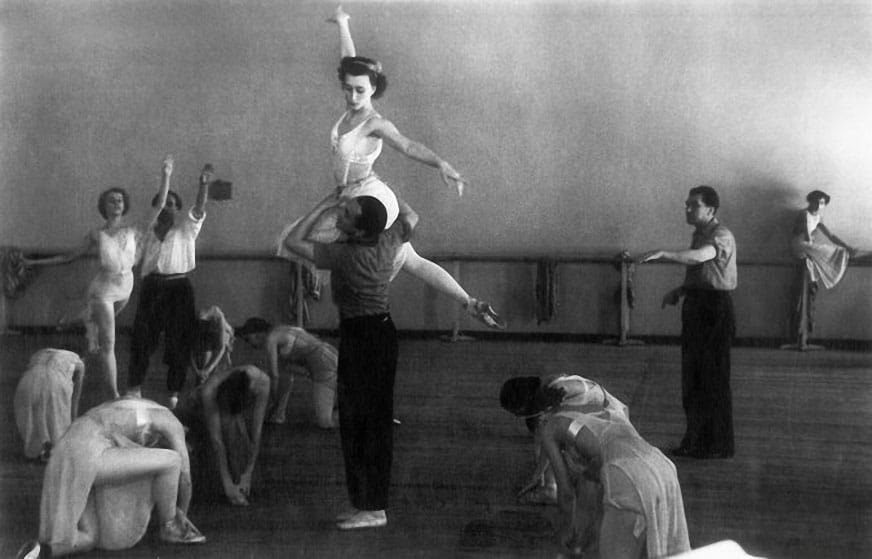

Archives are treasure troves for historians, but what can a historian of ballet — an art transmitted from dancer to dancer, foot to foot — do with a collection of gas and electricity bills, leave applications, fire damage reports and rejected libretti? Plenty, Mr. Morrison’s book shows. And who said that history should be a history of achievements? Mr. Morrison gives the story of the “Swan Lake” disaster a thorough and thoughtful treatment.

Inevitably, any backstage history becomes a history of people, often primarily of the unhappy ones.

“More is known about the scandals than the glories of the Moscow stage,” Mr. Morrison writes, “because the scandals generated heaps of documents.” We learn about sex slavery practiced in the imperial times and, in poignant detail, about the 1847 gang rape of the dancer Avdotya Arshinina; a string of leave applications gives us an idea of ballet as a form of hard labor; we are also reminded of the Bolshoi dancers’ strike in 1995.

To organize from the multitude of competing voices (each with its own story and each ready to tell everyone else’s stories), a clear and fascinating narrative is one problem “Bolshoi Confidential” successfully resolves; another, with which Mr. Morrison struggles at times, is to walk the fine line between oral history and gossip. That, in 1882, seven female costumes for Wagner’s “Tannhäuser” were purchased but never seen is a legitimate piece of historical evidence related to shady dealings at the Bolshoi.

But what do we do with the fact (if it is a fact) that Michael Maddox, the Bolshoi’s founder, once had a visitor, Sir Richard Worsley, whose estranged wife, Seymour Fleming, was rumored to have taken more than two dozen lovers in 1782 alone? A recent political mantra comes to mind: Stay on message.

The main problem with gossip is not even that it is often irrelevant and possibly wrong, but that it is simplistic, and tends to turn people into two-dimensional villains or buffoons. Some of the book’s characters, especially those cast in secondary roles, seem unrealistically flat: the imperial ballerina Matilda Kshesinskaya comes off as a promiscuous demon; the Soviet superstar Galina Ulanova, a medal-hunting hypocrite; Mikhail Mordkin is described as “an exhibitionist dancer who left the Bolshoi for the circus.”

Performing in circus venues was part of life for all ballet dancers touring across the globe. But to pick this one detail from Mordkin’s career (which culminated in his founding a company later known as the American Ballet Theater) seems a choice impoverished by gossip.

This anecdotization of history is a byproduct of Mr. Morrison’s otherwise winning strategy of peeping through the keyhole. Breathtakingly complicated life stories of both people and productions parade through the pages of “Bolshoi Confidential.” But the keyhole approach becomes less convincing when applied to Russian history and culture at large. While it may be occasionally eye-opening, it inevitably distorts the bigger picture. Cultural figures and processes find themselves in danger of being myopically reduced to their relation to the ballet stage, as happens occasionally, and visibly, under Mr. Morrison’s pen.

Take a list of writers, literary critics and social thinkers — Sergey Aksakov, Vissarion Belinsky, Aleksandr Herzen, Mikhail Saltykov-Schedrin — all described in the book as “prominent theatrical observers.” Albert Einstein and Sherlock Holmes gained prominence in their own fields; should we list them as “prominent amateur fiddlers”?

Or take a group of Russian merchants — the ones that gave Maddox a building loan — portrayed here as operatic “barrel-bellied, bearded boyars.” Merchants and boyars are not the same animals, historically. In the epoch when the Bolshoi was built, boyars didn’t exist in Russia anymore; their 18th-century descendants shaved, and liked to wear wigs.

Thankfully, 18th-century merchants and 19th-century men of letters are mere extras in Mr. Morrison’s backstage story; its central figures, like Plisetskaya, jump off its pages complex and alive.

Comments

Janeece

| 2017-01-13 16:13:15Arciltes like this just make me want to visit your website even more.

Reply to comment

The Russian Resolution

| 2017-01-14 15:00:28Thank you for your comment. The article isn't ours, of course, but we do try to find items to share that are likely to be of interest and value to our visitors. Please do come back for more information about Russia, in all its varieties.

Reply to comment

Add comment