Photographer Matteo Lonardi and reporter Antoaneta Roussi visited Russian artists in their studios to shoot their portraits and speak to them about their work, the art scene and creative censorship.

Many of the artists, based in and around Moscow and St Petersburg, once displayed their work in public spaces, but faced with increasing censorship there, some now feel more comfortable retreating to their private studios.

Abstract artists who live and work in St Petersburg, Kulkov and Dmitrieva often collaborate to create works inspired by the patterns seen in corals and craters, using paint and collage.

The couple were born in the age of perestroika, a time when Mikhail Gorbachev was Soviet leader and radical political innovation took place. Neither artist became attached to Soviet ideology, and Kulkov says there are too many young artists today engaging in what he describes as “Soviet porn”.

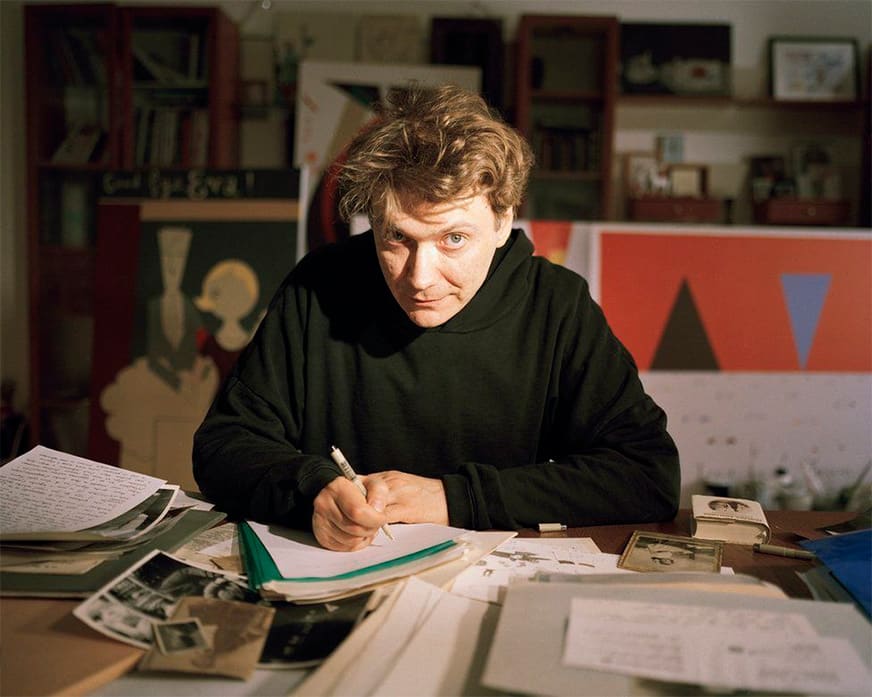

An artist and writer who comes from a distinguished cultural family, Pepperstein grew up in a tight-knit creative circle of artists, who gathered in secret during the Soviet era.

In his work he creates imaginary worlds where a “big red cube” in the Pacific Ocean is the headquarters of the government of Earth in 2555, with an undertone of the present political and societal landscape in Russia.

The main difference between the time of communism and capitalism in Russia is the relationships between people, he believes.

“People love each other less. Before, there was a certain cosiness inside [artistic] circles… people paid more attention to their spiritual lives.”

A Ukrainian-born Russian performance artist and sculptor based in Moscow, Kulik was one of the first performance artists in Russia, starting out on the streets of Moscow in the 1990s.

Throughout his career he has tested the boundaries of art and political activism. His best-known performance involved going naked on all fours and barking like a dog, to comment on the hypocrisy of America’s embrace of the new Russia.

He left the country for several years after Vladimir Putin first became president and believes the 1990s were the only years that artists had true freedom in recent Russian history.

“After the fall of Communism, there were no galleries, no art foundations, no institutions or collectors, nothing,” he said. “It was in the 1990s that the performance artists created this territory of art in Russia.”

Frolova is a visual artist who uses colourful latex in art performances and sculptures. She says her work tries to blur the boundaries between electropop music and art performance.

“My work is always bright and fun, because I like to add colour to otherwise grey and boring landscapes,” she said in her apartment, which faces the skyscraper business district of Moscow. “Its purpose is to make people escape reality.”

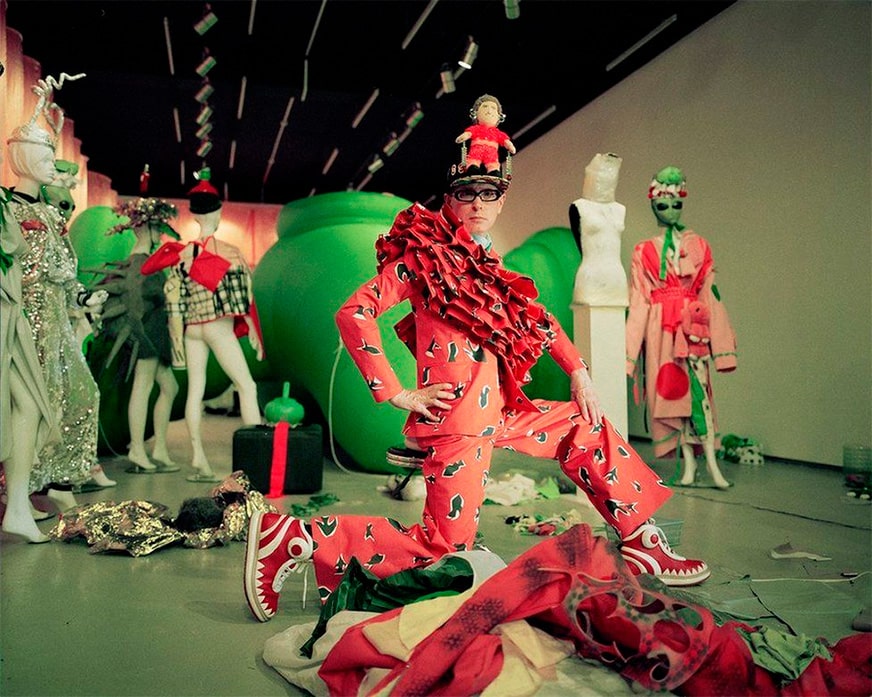

Bartenev is an artist, designer and pop icon. He creates absurd, colourful and provocative carnival fantasies using theatrical costumes and inflatable sculptures.

He believes that the 1990s was the most interesting time for art in Russia because the Iron Curtain had come down, but the big American and European brands had not yet entered the country.

“It changed completely, the whole mentality of Russians changed,” says Bartenev, while sewing outfits for an installation at the Burning Man festival in the US.

Kovylina is a controversial performance artist who focuses on Russian identity and women’s issues.

In one of her most-noted performances she wore a Russian military outfit, while dancing with various men from the audience and drinking two litres of vodka in the process. Her aim was to highlight the cliche of the Russian woman in post-Soviet society.

Now a mother of three, Kovylina has put her radical art to one side and lives in a rural village near Moscow with her husband, father and young boys.

“My success as an artist is related to my career in the West. In Russia they hate me… like any free woman,” she says.

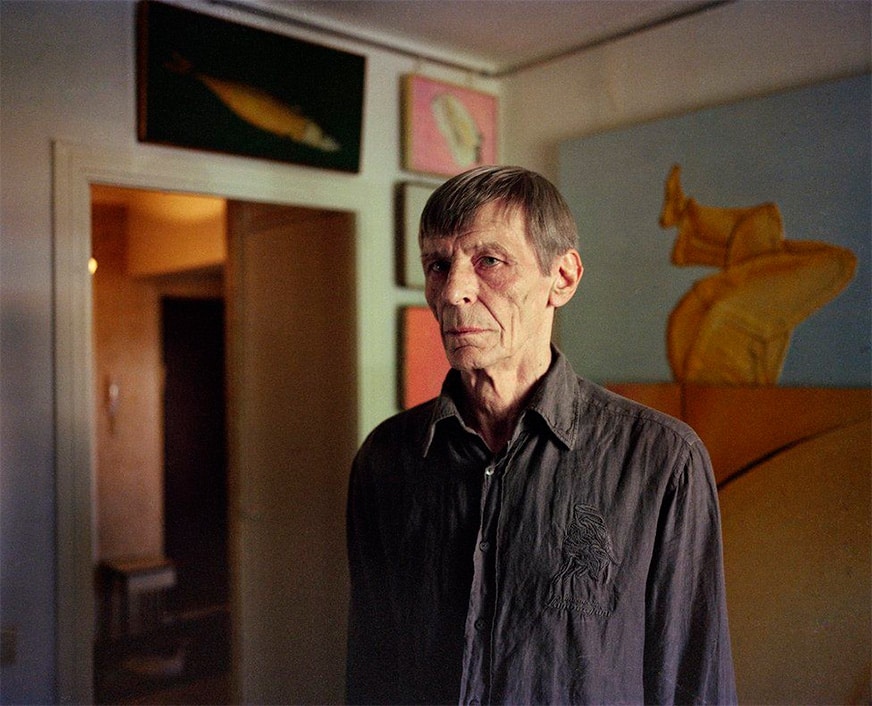

Born in a Siberian work camp during Stalinism, he moved to St Petersburg in 1966 and became involved with the underground art scene.

A still-life painter, all of his work features the same objects, representing life’s primary roots: an apple, bread, fish, an egg, a bottle, a skull, and a glass.

He combines the objects in different compositions, inspired by a branch of mathematics called combinatorics, which deals with counting.

Valran compares being an artist today to the former Soviet era: “Back then, there used to be ideological pressure. Now there’s pressure of the economic kind and the ideological pressure has also returned.”

Korina creates large-scale installations exploring the transformation of Russian urban spaces.

Her work looks at the way Russians feel towards Soviet monuments and buildings, which some people previously detested but now love because they represent a more structured and less financially competitive era.

Korina also looks at perpetual celebration in Moscow’s streets, which the government creates by putting on floral and light displays.

“It’s a very old fashioned idea, like from pagan times,” she says in her Moscow studio. “When people take part in this celebration culture, it gives permission for the government to decide everything else.”

Osmolovsky started his career as one of the first performance artists in Russia. He was part of a group called Against All who performed political pieces in the early 1990s. He is now an art professor and critic.

He is convinced that most of the political issues that Russia is facing now, internally and with its neighbours, are the result of the slow collapse of the former empire.

“The problem when a big country like the Soviet Union collapses is that the pieces that fell apart will start fighting with each other.”

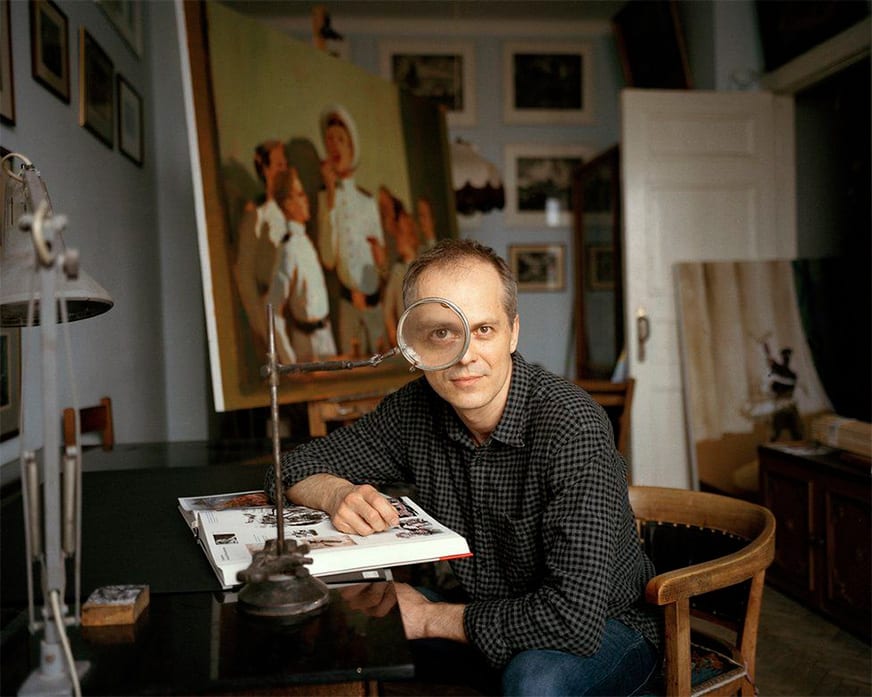

Razumov’s grandfather was commissioned by Joseph Stalin to illustrate the Canterbury Tales during World War Two to improve relations with the British.

He is known for his graphic illustrations but he also paints, using socialist realism to ironically criticise the contradictions of today’s Russia. He thinks that there is a larger identity crisis happening the world over.

“When the Soviet Union collapsed, we were all like immigrants in our own country,” he said in his grandfather’s studio, steps away from the Kremlin. “But now I think this identity crisis is common everywhere because of the huge technological changes happening in society.”

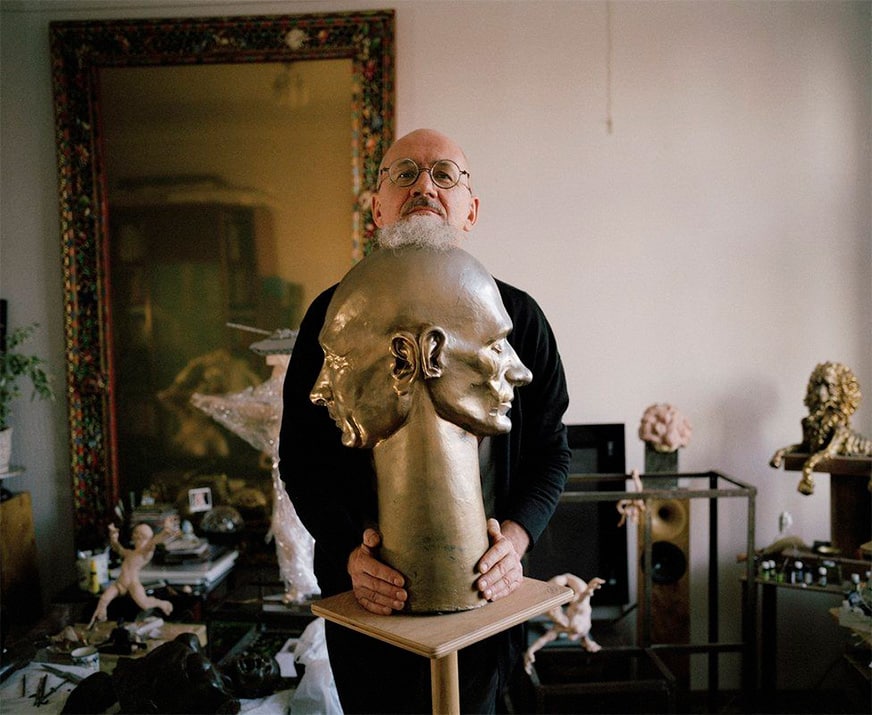

Masharov is a sculptor who has spent his life as a recluse amidst the bustle of Moscow.

In his barely-heated studio in the dedicated building of the Union of Russian Artists (once the Union of Soviet Artists) Masharov has created beige-coloured sculptures for decades. They are mostly human forms, with some of his pieces now in the collections of the Treytyakov Gallery, the Russian Museum and the Ludwig Museum.

He sees his work as his “understanding of life”.

Hyperrealist artists based in a small town outside of Moscow, they use their work to explore the themes of modernity, and Korshunov focuses on Christian themes. He was part of the team of artists that painted murals inside the Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Moscow.

Korshunov says that since the early 1990s what has changed most for Russian artists is that now there is a consumer base, whereas in the Soviet Union only those with connections could acquire art.

“You could only encounter official art in designated cultural rooms in large institutions or in museums,” said Korshunov. “Today anyone can buy it.”

Comments

Add comment