Undeterred by sanctions and optimistic about Donald Trump, German companies are rushing back in, hopeful for an economic recovery.

In the past two years, plunging oil prices and U.S. and The European Union sanctions on Russia for its intervention in Ukraine sent foreign investors fleeing. Now, Western firms are placing new bets that Russia, which has been battered by economic turmoil, is on the verge of an upswing.

German companies are leading the way, as they have in the past. Businesses ranging from blue chips such as Daimler AG and Henkel AG to lesser-known niche players are embarking on new investments.

“There are rock-solid economic reasons why companies invest there now,” said Oliver Hermes, chief executive of German family-owned pump maker Wilo SE, which built a €35 million ($37.6 million) plant in Moscow that opened this year.

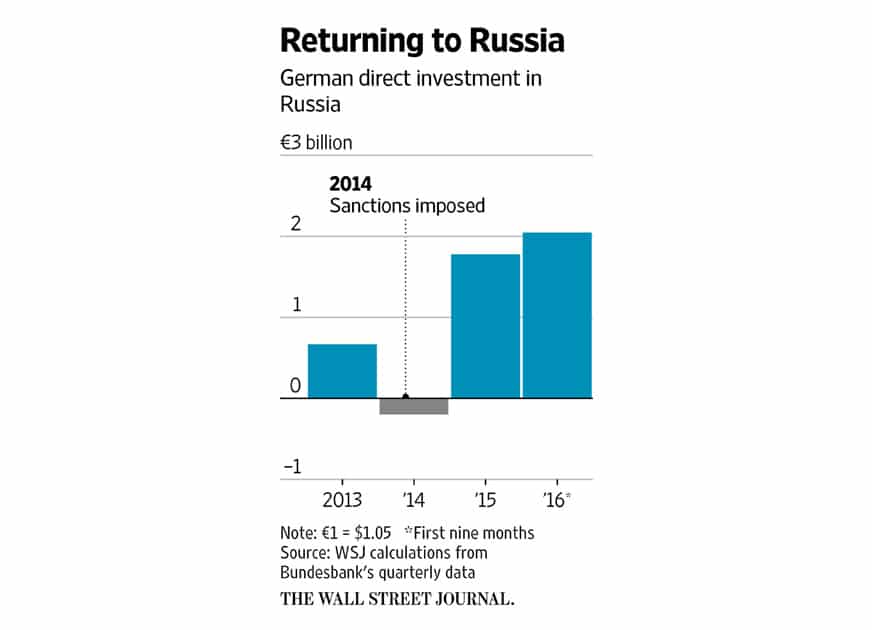

Direct investment by German companies in Russia rose to €2.05 billion in the first nine months of the year. That surpasses the amount for all of 2015 and contrasts with a net outflow in 2014, according to statistics from Germany’s central bank.

Among the reasons for the return: a weak ruble that German executives say has made labor cheaper than in China and Russia’s efforts to woo—and sometimes coax—Western businesses into ramping up investment.

German companies have done business in Russia since the czarist era. While some bonds have been strained amid a frosty relationship between Chancellor Angela Merkel and Russian President Vladimir Putin, few were severed. Joe Kaeser, chief executive of industrial conglomerate Siemens AG, visited Mr. Putin at the beginning of the Ukraine crisis in 2014, sparking outrage in Berlin.

Some firms are considering building new plants while others are completing projects they put on ice after the U.S. and EU imposed sanctions on Russia for its annexation of Crimea. EU leaders are expected to extend sanctions for another six months before they expire in January, officials say.

Syria is also a lingering concern. Western leaders this past fall warned Russia they may impose additional sanctions because Russia supported the Syrian government’s siege of Aleppo. But EU leaders have yet to take concrete action.

While conditions for doing business in Russia are improving, access to financing remains tough, experts say. Local competitors often lobby hard against foreign newcomers, and new Russian regulations set conditions for foreign firms operating in the country.

“Besides the red carpet, firms are also exposed to considerable pressure, and that, they don’t like so much,” said Matthias Schepp, head of the German-Russian chamber of commerce AHK.

Despite these concerns, German car maker Daimler AG is in talks with the Russian government about building a factory. Volkswagen AG last month began production of its Tiguan compact sport-utility vehicle at its plant in Kaluga, southwest of Moscow, following a decision in 2013 to invest €1.2 billion to modernize the plant. Henkel AG, a maker of industrial and consumer staples, meanwhile opened a new €30 million detergent plant in the city of Perm in June.

It is not just German firms going back into Russia. Total foreign direct investment into the country was $7.12 billion in the second quarter, according to Russia’s central bank. That compares with $6.48 billion for all of 2015, which was a sharp decline from $22.03 billion in 2014 and a record $69.22 billion in 2013.

Germany has been the second-biggest investor in Russia this year, behind China, with investments in 35 new projects, according to the Russian Direct Investment Fund, a sovereign-wealth fund set up to help finance international investment in Russia.

An AHK survey from October showed that 22% of German member companies were planning to invest significantly more in their Russian production facilities in the coming 12 months.

Part of the renewed interest is due to finely calibrated incentives crafted by Moscow to entice Western companies.

A recent Russian government decree strengthens pre-existing legislation that forces state companies to prioritize domestic suppliers starting Jan. 1. At the same time, the government is offering foreign firms that sign a “Special Investment Contract,” which includes a pledge to invest at least 750 million rubles ($11.8 million) in the country, the same status as domestic producers, making them eligible to apply for state contracts and special tax benefits.

German farming-equipment maker CLAAS KGaA was the first company to sign such a contract in June. Although its sales in Russia have dropped by 40% since Russia was slapped with sanctions in 2014, the company built a €120 million plant in Russia last year—its biggest investment ever outside Germany.

“We need this status to keep the playing field level,” said CEO Lothar Kriszun. “Otherwise, it wouldn’t be viable for a company like us.”

CLAAS negotiated for nearly a year to obtain the status and is sanguine about the market’s prospects. In 2017, it expects Russia sales to grow again and aims to double production at its new plant this year, he said.

Some are hoping for a thaw on the political front, too, after Donald Trump’s election as U.S. president, a post he is to assume in January. Mr. Trump has said he wants to repair ties with Russia.

Siemens, which had to pare back its business in Russia to comply with sanctions, signaled last month that it would re-engage with Russia if the political skies cleared.

Siemens would like to “help the country to be rebuilt,” Mr. Kaeser said during a press conference, referring to Russia’s aging infrastructure.

“Now there are signs of a detente with the West,” said Mr. Hermes of Wilo. “If you look at Mr. Trump’s promises, it seems that at the very least there are going to be discussions again.”

Comments

Add comment